-

Publish Your Research/Review Articles in our High Quality Journal for just USD $99*+Taxes( *T&C Apply)

Offer Ends On

Menaka Das* , Gitanjali Panda , Ganesh Chandra Gan

Corresponding Author: Menaka Das, Ph.D. Research Scholar in Economics, Department of Social Science, Fakir Mohan University, Balasore, Odisha-756089, India.

Received: January 22, 2026 ; Revised: January 27, 2026 ; Accepted: January 29, 2026 ; Available Online: February 06, 2026

Citation:

Copyrights:

Views & Citations

Likes & Shares

Climate change has emerged as a critical determinant of population mobility and socio-economic vulnerability, particularly within environmentally fragile regions. This study examines the out -migration patterns from Bhadrak and Bhubaneswar urban cities of Odisha, employing secondary data derived from the Census of India. Bhadrak, a coastal district recurrently exposed to cyclones, floods, and salinity intrusion, faces persistent livelihood disruptions that compel rural populations to migrate in pursuit of economic stability. Conversely, Bhubaneswar, the state capital and a rapidly urbanizing center, also experiences notable out-migration, primarily driven by urban stress, precarious employment, and rising living costs. The analysis focuses exclusively on the scale and spatial dynamics of out-migration, while existing literature is integrated to contextualize the associated socio-economic insecurities linked to climate-induced mobility. The study reveals that the Eastern Region recorded the highest proportion of out-migrants from both Bhadrak (7.68%) and Bhubaneswar (24.90%), highlighting strong socio-economic linkages with West Bengal and Bihar. Female migration was mainly influenced by marriage and family movement, while male migration was largely employment-oriented. Work-related migration has been the dominant reason towards migrating Southern and Western regions of India, whereas educational migration has been higher towards the Northern and Eastern regions of India. Bhadrak’s migration pattern remains socially driven, whereas Bhubaneswar’s reflects economic motives, indicating distinct urbanization trajectories. Strengthening employment, education, and regional integration policies is vital to balance and manage migration flows across Odisha’s urban centers.

Keywords: Climate Change, Migration Patterns, Out-Migration, Socio-Economic Insecurities

JEL Classification: Q54, I32, J61

INTRODUCTION

Climate change has emerged as one of the most significant global challenges influencing patterns of human mobility in the twenty-first century. Increasing temperatures, erratic rainfall, sea-level rise, and the growing frequency of extreme weather events have disrupted livelihood systems, particularly in developing countries where economies remain predominantly agrarian. Migration, both internal and international, has increasingly become an adaptive response to these environmental stresses (IPCC, 2022)[i]. Global estimates suggest that climate-related events could displace up to 216 million people by 2050, with South Asia identified as one of the most vulnerable regions due to its high population density and climate sensitivity (World Bank, 2021)[ii]. Consequently, the intersection between environmental change and migration has gained scholarly attention, especially concerning its implications for poverty, inequality, and social security (IOM, 2020)[iii].

In India, climatic variability significantly influences rural livelihoods, employment, and settlement patterns. The country experiences recurrent floods, droughts, and cyclones, which often result in the loss of agricultural productivity and displacement of population groups dependent on climate-sensitive occupations (Dasgupta et al., 2023). Among Indian states, Odisha occupies a particularly vulnerable position due to its long coastline and exposure to multiple climatic hazards. The state has faced several severe cyclonic storms in recent decades—such as Phailin (2013), Fani (2019), and Yaas (2021) causing widespread destruction of property, infrastructure, and livelihood assets (Odisha State Disaster Management Authority, 2022). Coastal erosion, saline water intrusion, and repeated flooding have forced many households to migrate temporarily or permanently in search of stable livelihoods. Simultaneously, urban centres such as Bhubaneswar have experienced increasing in-migration, reflecting broader patterns of rural–urban migration within the state (Census of India, 2011)[i].

Despite the growing attention on climate-induced migration, existing literature on India remains largely focused on national or macro-regional analyses, often overlooking micro-level and district-specific dynamics (Rajan & Narayan, 2020)[ii]. Few studies have examined how climate variability interacts with socio-economic insecurities at both the origin and destination points of migration within the same regional context. Moreover, empirical investigations integrating climatic, demographic, and socio-economic indicators remain scarce for Odisha, where local-level differences in exposure and adaptation capacities are substantial (Panda & Mohapatra, 2021)[iii]. Addressing this research gap requires an analytical framework that connects climate vulnerability, migration patterns, and livelihood insecurity through comparative district-level analysis.

Against this background, the present study selects two contrasting urban cities of Odisha—Bhadrak and Bhubaneswar (Khordha) to understand the multi-dimensional nature of climate-induced migration and its socio-economic consequences. Bhadrak, located in the coastal belt, is characterized by high exposure to cyclones, floods, and saline intrusion, making it an important origin area of out-migration. Conversely, Bhubaneswar, as the state capital and an emerging urban hub, functions as a major destination for migrants from both coastal and inland districts. The comparative approach adopted in this study allows examination of both “push” factors driving migration in the hazard-prone coastal region and “pull” dynamics shaping migrant experiences in the urban context.

In this study, the primary objectives are;

LITERATURE REVIEW

This section highlights the existing studies on migration patterns and the socio-economic insecurities experienced by migrant populations. It reviews previous research to understand how climate change, livelihood stress, and urbanisation influence migration decisions and shape the living conditions of migrants in urban areas.

Moharaj et al. (2025)[iv] find that declining rainfall and agricultural collapse in Meenakshipuram have intensified economic hardship, leading to large-scale migration and abandonment of villages, stressing the role of socio-economic inequality and weak governance in worsening climate impacts. Gupta et al. (2025)[v] reveal that migration in India and Bangladesh is primarily driven by environmental stress and socio-economic vulnerability, particularly in coastal regions, and highlight the inadequacy of current adaptation measures for long-term resilience and protection. Ghatak (2021)[vi] finds that climate-induced disasters have become a major force behind forced migration in India, disproportionately affecting marginalized groups such as women, the elderly, and the poor. Mishra (2017)[vii] identifies Odisha as highly climate-sensitive due to recurring disasters that deepen poverty and hinder growth, calling for collaborative, climate-resilient development efforts. Similarly, Sahu (2017)[viii] shows that temporary migration functions as a key adaptation strategy to drought-induced livelihood losses in Odisha, with women bearing increased burdens due to male outmigration. Bhagat (2017)[ix] links climate vulnerability with migration, noting that coastal regions show high in-migration while drylands experience severe out-migration, suggesting migration as an adaptive response. Kalinga (2020)[x] highlights large-scale displacement in Satavaya, Odisha, due to sea-level rise, exacerbated by low awareness and poor institutional support. Das (2025)[xi] finds that rising temperatures, cyclones, education, income, and landholding significantly influence migration decisions in the Indian Sundarban, urging targeted adaptation policies. Khairkar and Mahapatra (2025)[xii] identify flood exposure as a major driver of migration across Indian states, with Assam and Madhya Pradesh being most vulnerable, and show a strong positive link between migration and vulnerability levels.

Kaczan and Orgill-Meyer (2020)[xiii]review global migration responses to climate shocks, revealing that migration patterns depend on household capacity and event type, with poorer households often trapped in place. Piguet et al. (2011)[xiv] provide a global overview of the climate–migration nexus, stressing the interaction of environmental, social, and political factors and the need for legal recognition of climate migrants. Bardsley and Hugo (2010)[xv] conceptualize migration as a proactive adaptation strategy to environmental stress rather than failure to cope. Hassani-Mahmooei and Parris (2012)[xvi] project that 3–10 million people in Bangladesh may be displaced internally due to droughts, cyclones, and floods, underscoring the need for adaptive policy frameworks. Milán-García (2021)[xvii] notes a rise in global climate–migration research with increasing focus on justice, sustainability, and human rights. McLeman (2017)[xviii] emphasizes that climate-induced migration outcomes depend on socio-economic and political contexts, requiring urgent legal and policy reforms. McMichael (2013)[xix] links climate change and food insecurity, finding that climate shocks drive migration while also creating new insecurities at destinations. Ezeagbanari (2025)[xx] observes that insecurity and unemployment in Nigeria have intensified international migration, aggravating poverty and underdevelopment. Bilmez and Umutlu (2025)[xxi] stress that climate-driven migration causes economic and infrastructural strain, calling for integrated global policies and climate finance. Falco (2018)[xxii] underlines agriculture as a mediating factor in climate-induced migration and calls for more structural and food-security-focused research. Piguet and De Guchteneire (2011) further argue that migration linked to environmental stress must be approached through human rights and global governance lenses. Memon et al. (2018)[xxiii] report that rising temperatures and erratic rainfall in Tharparkar have worsened food and water insecurity, increasing women’s vulnerability. Stoler et al. (2021)[xxiv] identify household water insecurity as an overlooked yet critical driver of climate migration, suggesting that improving water management can reduce displacement. Rana and Ilina (2021)[xxv] find that climate-induced migration has placed pressure on Bangladeshi cities, advocating for integrated rural–urban resilience planning. Finally, Pillai (2025)[xxvi] concludes that climate-related migration stems from complex social, environmental, and personal dynamics, intensifying existing inequalities and demanding inclusive, rights-based, and interdisciplinary policy interventions. The interplay between climate vulnerability and migration creates a multifaceted nexus of socio-economic insecurities, as underscored by recent studies from India and South Asia. Biswas and Nautiyal (2023)[xxvii] argue that socio-economic vulnerability is strongly influenced by political and structural factors, with eastern India emerging as the most vulnerable region. Tewari (2023)[xxviii], in The Indian Journal of Social Work, examines how environmental pressures in the Sundarbans Delta such as- rising salinity and recurrent flooding reshape household structures and livelihood systems.

The study highlights that these climatic disruptions not only compel population movements but also intensify existing gender and income disparities, particularly affecting women-led households that remain behind. Likewise, Sarkar, Joshi, and Yamini (2024)[xxix], in the Journal of Informatics Education and Research, analyse migration patterns in Odisha and West Bengal, demonstrating that climatic stresses like drought, flood, and declining crop productivity serve as critical triggers for out-migration. Their findings reveal that migrants frequently experience precarious working conditions, inadequate housing, and social marginalisation in urban destinations, reinforcing the idea that environmental vulnerability often translates into urban socio-economic instability. In a related perspective, Mohanty et al. (2024)[xxx], in their IAI Nexus25 Brief, discuss how weak institutional mechanisms and insufficient adaptive capacities heighten the vulnerabilities of climate-affected migrants, leaving them exposed to livelihood disruptions and social exclusion. Similarly, Choksey (2023)[xxxi], writing in the International Journal of Social Science and Economic Research, investigates the impacts of climate-driven displacement on urban-village communities in Beed, revealing that forced mobility under environmental stress erodes community resilience and deepens urban poverty, joblessness, and housing insecurity.

Complementing these findings, the article “Vulnerabilities of Climate Change-Induced Displacement and Migration in South Asia” (2025) published in Discover Global Society synthesises regional evidence to show that climate-related migration is intertwined with multiple insecurities, including unstable incomes, deteriorating health conditions, and weakened social networks, particularly among economically and socially marginalised populations. Collectively, these studies reinforce the core objective of this research to examine the socio-economic insecurities associated with migration in contexts of climatic stress by demonstrating that climate-induced migration is not solely a spatial or demographic process but a broader socio-economic transformation marked by uncertainty, fragility, and institutional inadequacy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study adopts a descriptive and analytical research design and focuses exclusively on urban out-migration from two distinct urban centres of Odisha Bhadrak (Urban) and Bhubaneswar (Urban). The selection of these urban cities is purposive, representing two contrasting migration environments. Bhadrak, located in the northern coastal region, experiences frequent cyclones, floods, and saline water intrusion, which disrupt livelihoods and trigger environmentally induced out-migration. In contrast, Bhubaneswar, the capital city of Odisha, represents a rapidly urbanizing centre characterized by better employment prospects, infrastructure development, and service sector expansion, influencing different migration motivations and directions.

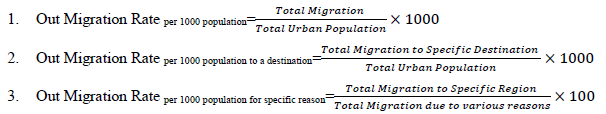

The study relies entirely on secondary data to ensure consistency, reliability, and comparability. Data were obtained primarily from the Census of India, 2011, specifically from the D-Series Migration Tables. Key Indicators derived from Census include migration rate, place of last residence (Rural-urban, urban-urban, rural-rural) duration of residence (less than 1 year,1-4 years etc), and reasons for migration (employment, education, marriage, moved after marriage and others) and gender composition of migrants (sex-wise distribution of migrants). Socio-Economic indicators such as literacy level, housing conditions, access to basic amenities such as drinking water, sanitation and electricity, gender disparity in work participation and migration and marital status these indicators collectively reflect the socio-economic insecurities that influence and are influenced by migration patterns in the study area. In addition, relevant information was collected from the District Census Handbooks of Bhadrak and Bhubaneswar to supplement demographic and socio-economic details. The analysis concentrates on urban out-migrants that is, individuals whose last place of residence was in urban areas of Bhadrak or Bhubaneswar but who have migrated to other rural or urban regions within India. The data were systematically compiled, tabulated, and analysed through percentage distribution and regional comparison to capture variations in gender composition, migration reasons, and destination patterns. Basic statistical tools such as percentage distribution and ratio analysis were employed to interpret regional, gender, and reason-specific patterns. The study focuses on Bhadrak, a medium-sized town with limited industrial and educational infrastructure, and Bhubaneswar, the state capital with diversified employment and educational opportunities. This approach enables a comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing urban out-migration and highlights the contrasting migration dynamics between a coastal district (Bhadrak) and an urban capital centre (Bhubaneswar). Out-migration rate was calculated by the following formula;

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Patterns of Migration

This section presents the results derived from the secondary data sources, primarily the Census of India (2011) and District Census Handbooks (DCHB) for Bhadrak and Bhubaneswar districts. The analysis of urban out-migration from Bhadrak and Bhubaneswar presents a distinct pattern of regional, economic, and gendered mobility reflecting diverse socio-environmental and developmental contexts. Drawing upon the Census of India (2011) migration tables, the study reveals that the Eastern, Central, and Northern regions constitute the predominant destinations for out-migrants from both districts, albeit driven by different underlying motivations.

In the case of Bhadrak, a coastal district frequently affected by cyclones, floods, and saline intrusion, migration is largely driven by push factors related to livelihood disruption and climate vulnerability. The data indicate that a major share of male migrants move in search of work and employment opportunities, reflecting distress-induced economic mobility. Conversely, female migration is predominantly explained by marriage and household movement, reinforcing the social and cultural dimensions of migration in rural and semi-urban contexts. Bhubaneswar, on the other hand, demonstrates a more diversified migration profile characterized by pull-driven factors. As a rapidly expanding urban centre, it generates out-migration linked to employment diversification, business expansion, and higher education. A rising proportion of female migrants seeking educational and professional opportunities marks a gradual transformation towards aspirational migration, indicative of changing gender dynamics in urban mobility. Overall, the comparative assessment highlights that while Bhadrak’s out-migration is compulsion-driven and economically motivated, Bhubaneswar’s is opportunity-oriented and development-driven. The predominance of household-based movement in both districts underscores migration as a collective adaptive strategy rather than an individual decision. These findings emphasize the necessity of region-specific policy interventions focusing on livelihood resilience, climate adaptation, and inclusive urban planning to ensure sustainable migration governance in Odisha.

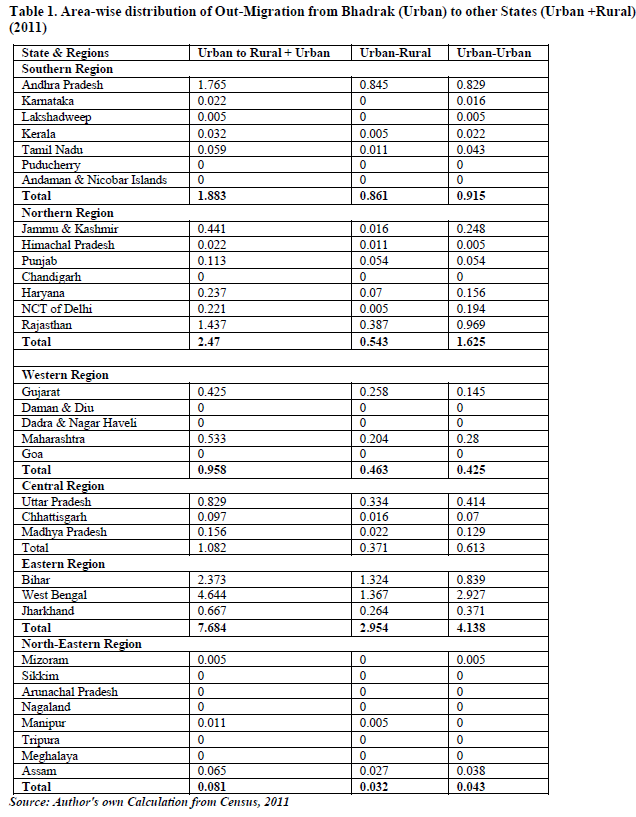

The analysis of Table 1 shows that in 2011, urban out-migration from Bhadrak was mainly directed toward the eastern states particularly West Bengal, Bihar, and Jharkhand which together accounted for the majority of outflows, with West Bengal as the leading destination due to geographical proximity and socio-economic ties. Moderate migration occurred toward northern states like Delhi, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh, while smaller flows were recorded to southern and western states such as Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, and Gujarat. The findings indicate a predominance of urban-to-urban migration, reflecting the movement of people seeking employment in construction, services, and informal sectors, whereas urban-to-rural migration was limited and largely driven by social or familial factors. Overall, the trend underscores Bhadrak’s regionally concentrated, livelihood-oriented migration pattern within economically connected neighbouring states.

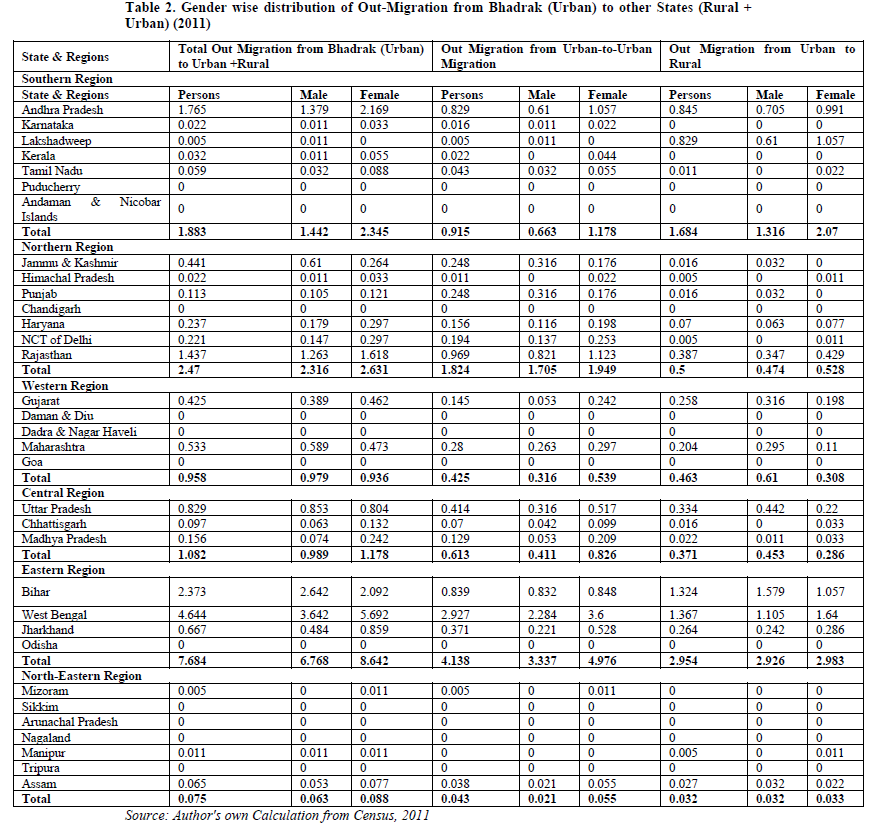

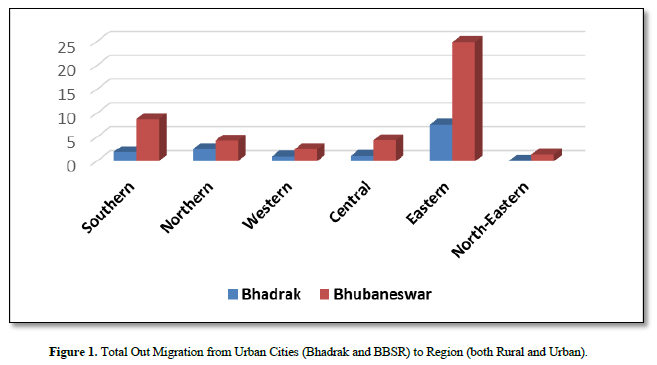

Table 2 shows that the Eastern Region attracts the highest out-migration from Bhadrak (7.68%), mainly to West Bengal and Bihar, indicating strong regional and social linkages. Both males (6.76%) and females (8.64%) migrate significantly, reflecting migration for work as well as family-related reasons such as marriage. The Northern Region ranks second (2.47%), with major destinations like Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi, where Urban-to-Urban migration is notably higher, driven by employment opportunities in cities. The Southern Region (1.88%) also records noticeable migration, especially to Andhra Pradesh, where female migration exceeds male migration, suggesting social and marital mobility. Migration to the Western (0.96%) and Central Regions (1.08%) remains moderate, directed mainly toward Maharashtra, Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh, likely for labour and livelihood purposes. The North-Eastern Region shows minimal migration (0.07%), indicating limited economic or social connections. Overall, Urban-to-Urban migration dominates across all regions, and gender differences suggest that males mostly migrate for employment, while females move primarily for marriage or family reasons. This pattern highlights both economic and social factors influencing out-migration from Bhadrak’s urban population.

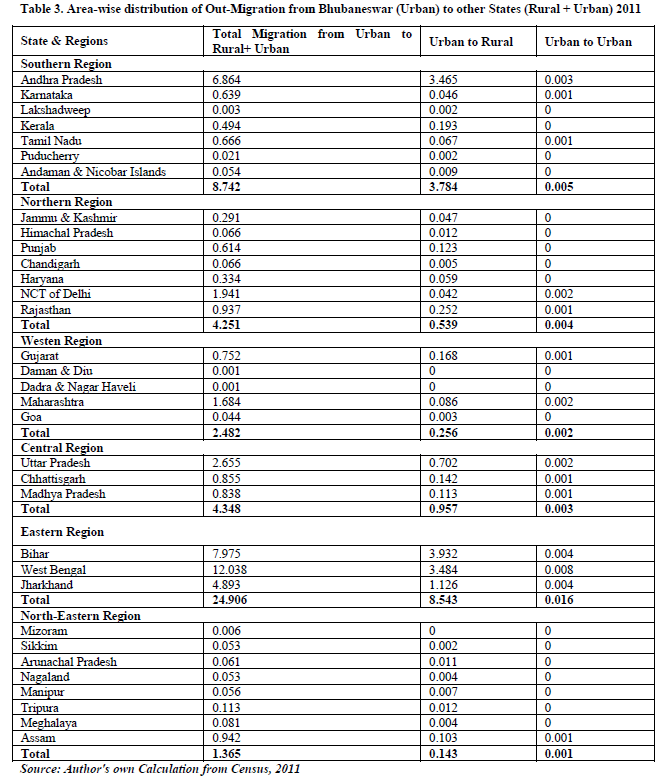

Table 3 shows the interstate out-migration from urban Bhubaneswar (2011) by destination state and by migration type. The results reveal a pronounced eastern orientation: more than half (54.0%) of Bhubaneswar’s interstate outflows are directed to the Eastern states (West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand), with West Bengal alone accounting for the largest single share (12.038 units). The Southern region is the second largest destination (18.97%), led by Andhra Pradesh. Notably, migration from Bhubaneswar to other states is overwhelmingly to rural or mixed (rural+urban) destinations rather than to other urban centres: the Urban→Rural component sums to 14.222 units while Urban→Urban movement is almost negligible (0.031 units). This pattern suggests that interstate migrants from Bhubaneswar are more likely to take up rural or peri-urban livelihoods (seasonal labour, agriculture, informal work) or move to family/kin networks outside large cities, rather than relocating to other metropolitan destinations. The geographic concentration in the East likely reflects proximity, established social networks and specific labour market opportunities; these findings point to the need for regionally tailored migration policies and further study into the drivers (economic, social and spatial) of Bhubaneswar’s interstate migration.

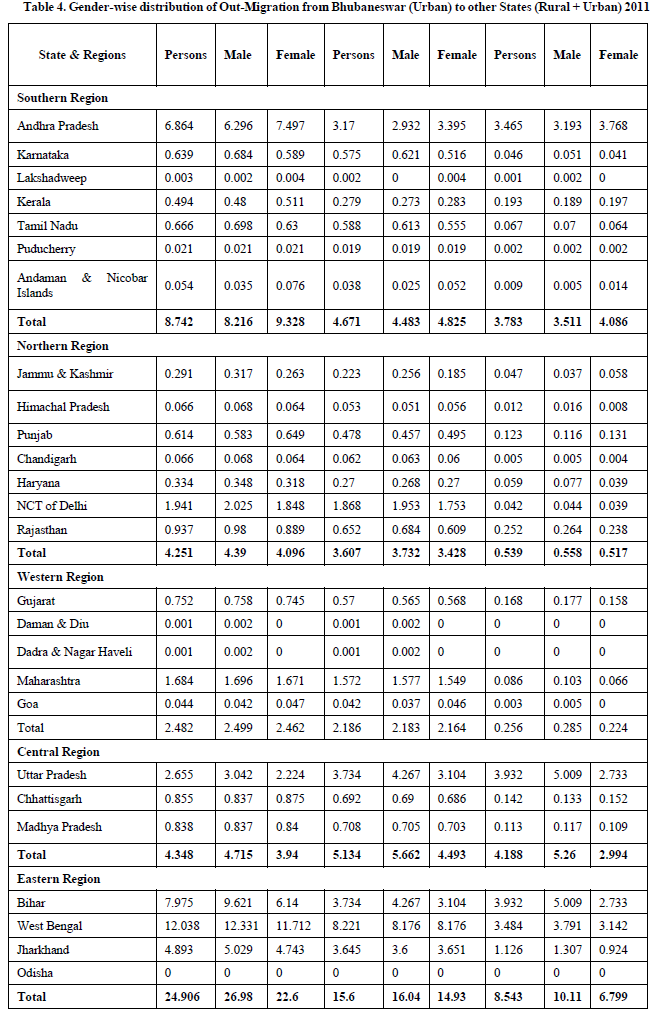

Table 4 represents the gender-wise distribution of out-migration from Bhubaneswar (Urban) to other States (Rural + Urban) during 2011. It provides a detailed breakdown of how male and female migrants from Bhubaneswar were distributed across different regions of India, highlighting variations in both the scale and direction of movement. The table classifies migration into three categories Urban to Rural + Urban (combined total), Urban to Rural, and Urban to Urban to capture the full pattern of spatial mobility. Each region, such as Southern, Northern, Western, Central, Eastern, and North-Eastern, is further divided into specific states, indicating the total number of migrants along with their gender composition. The data clearly define that migration from Bhubaneswar is not uniform across regions or between genders. The Eastern Region (comprising West Bengal, Bihar, and Jharkhand) records the highest out-migration, reflecting a strong male dominance, which is likely associated with employment-driven mobility. In contrast, the Southern Region (including Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and others) shows a comparatively higher share of female migrants, possibly influenced by marriage-related or family-associated migration. The Northern, Western, Central, and North-Eastern Regions show relatively balanced or male-dominated migration, but their overall shares remain smaller compared to the Eastern and Southern regions.

Overall, the table defines the structure of interstate and interregional migration flows from Bhubaneswar and demonstrates how migration is influenced by both geographical proximity and gender-specific factors. It indicates that male migration is largely work-oriented, whereas female migration is often linked to social and familial reasons. Hence, Table 4 serves as a vital indicator of gendered migration patterns from urban Odisha, reflecting the socio-economic dynamics and spatial dimensions of population movement during the 2011 Census period.

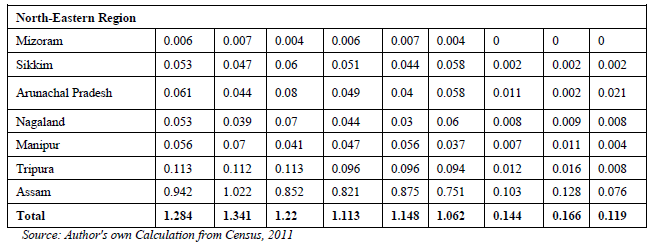

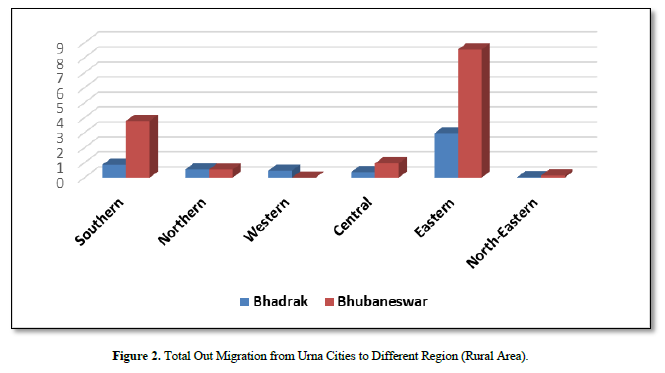

Table 5 presents the distribution of migration from two urban centres Bhadrak and Bhubaneswar towards different regions of Odisha, namely Southern, Northern, Western, Central, Eastern, and North-Eastern. The table categorizes these movements into three types: Urban to Rural–Urban, Urban–Rural, and Urban–Urban migrations. A close examination of the data reveals that the Eastern region emerges as the most significant destination for migrants from both cities. For Bhadrak, approximately 54.44 percent of the total urban outmigration is directed towards the Eastern region, while for Bhubaneswar, the share is slightly higher at 55.69 percent. This indicates that the Eastern part of Odisha acts as a major attraction for migrants, possibly due to better employment opportunities, social linkages, or improved living conditions.

In the case of Bhadrak, the total outmigration recorded is 27.14 units, out of which 52.16 percent falls under Urban to Rural + Urban migration, 19.25 percent under Urban–Rural, and 28.59 percent under Urban–Urban movement. This suggests that a considerable proportion of Bhadrak’s migrants are moving towards other urban destinations, particularly within the Eastern region where Urban–Urban migration is notably high (4.138 units). In contrast, Bhubaneswar records a much higher total migration value of 60.09 units, with the majority (76.70 percent) of the outflow occurring under the Urban to Rural + Urban category, followed by 23.25 percent under Urban–Rural, and a very negligible 0.05 percent under Urban–Urban migration. This clearly indicates that migrants from Bhubaneswar are predominantly moving towards rural or semi-urban areas rather than to other urban centres. Region-wise, after the Eastern region, the Southern region ranks second as a major destination, accounting for 13.47 percent of Bhadrak’s total migration and 20.85 percent of Bhubaneswar’s total. The Northern and Central regions show moderate shares, while Western and North-Eastern regions record relatively lower migration figures from both cities. Notably, the North-Eastern region receives the least migration flow, constituting less than 1 percent from Bhadrak and about 2.5 percent from Bhubaneswar, indicating limited connectivity or economic attraction in that part of the state. Overall, the table highlights a clear spatial pattern of migration wherein the Eastern region dominates as the preferred destination, followed by the Southern and Central regions. The data further illustrate that the nature of migration differs significantly between the two cities Bhadrak’s migration is more urban-oriented, whereas Bhubaneswar’s migration is largely rural or semi-urban oriented. These differences could be attributed to varying levels of urban saturation, employment structures, housing costs, and socio-economic factors influencing migration decisions in the two urban centres.

Reasons for Migration

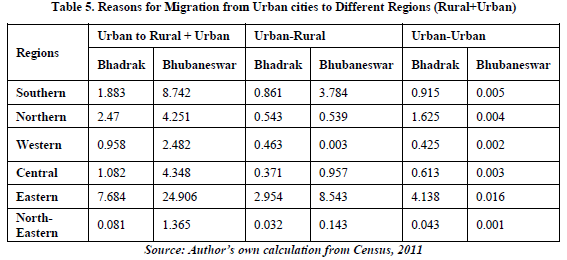

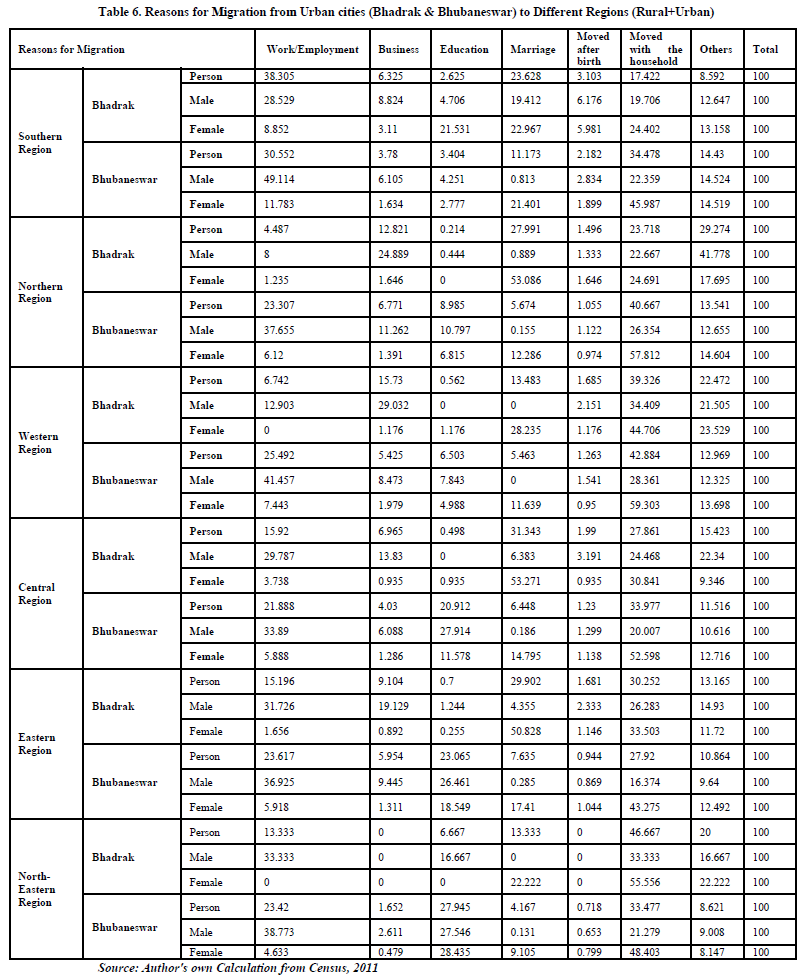

The Table 6 shows that people from Bhadrak and Bhubaneswar migrate to different regions for various reasons, and these reasons also differ between men and women. Overall, the main reason for migration from both cities is work or employment, especially toward the Southern, Eastern, and Central regions. For example, a large number of people from Bhadrak (38%) and Bhubaneswar (31%) moved to the southern region for jobs. Business-related migration is more common toward the Western and Northern regions, particularly from Bhadrak.

There is also a clear difference between men and women. Most men migrate for work or business, while most women migrate for marriage or move along with their families. For instance, more than half of the women from Bhadrak moved to the northern region after marriage, and many women from Bhubaneswar moved to the western and northern regions with their households.

Education-related migration is noticeable mainly from Bhubaneswar, especially to the Central and North-Eastern regions, while it is quite low from Bhadrak. In Bhadrak, a large number of people fall under the “other reasons” category, showing that some migration happens for mixed or unclassified causes.

In short, migration from both cities is mostly for livelihood and family reasons men move mainly for work, and women move mainly for marriage or family purposes. Bhubaneswar shows more education and family-related migration, while Bhadrak has more migration for business and other mixed reasons.

Analysis of urban insecurities & vulnerabilities in Bhubaneswar and Bhadrak

Odisha has undergone rapid urbanisation during the decade 2001–2011, with its urban population increasing from 37 million to 42 million, and the proportion of the urban population rising to 16.68 percent (Government of Odisha, 2023). This expansion, while indicative of economic growth, has simultaneously intensified challenges related to urban infrastructure, service delivery, and environmental security. Two prominent coastal cities—Bhubaneswar and Bhadrak illustrate these vulnerabilities. Bhubaneswar, located in Khordha district, records the highest urbanisation rate in the state (47 percent). The city covers an area of about 186 sq. km, with 67 wards and 46 revenue villages (Bhubaneswar Municipal Corporation [BMC], 2024). Large-scale rural-urban migration in search of employment and better services has led to the proliferation of informal settlements; nearly 40 percent of residents live in 180 slum pockets with limited access to clean water, sanitation, and adequate housing (Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies [IHS], 2022). Rapid growth and unregulated land use have resulted in environmental degradation, deforestation, rising heat levels, and encroachment on low-lying areas, which, coupled with poor waste management, increase the risk of urban flooding and vector-borne diseases. The city also faces recurrent climate-induced hazards such as cyclones, heat waves, and urban floods (World Resources Institute [WRI], 2021).

Bhadrak, a smaller coastal municipality, had a population of 107,463 in 2011, with the broader urban agglomeration reaching 129,228 (Directorate of Census Operations Odisha, 2011). The district’s economy remains primarily agrarian, making it vulnerable to floods, salinity, and cyclones, which frequently damage crops and infrastructure (Government of Odisha, 2023). Limited employment opportunities and seasonal agricultural distress drive significant outmigration, particularly among youth seeking jobs in other states such as Gujarat, West Bengal, and Andhra Pradesh. Indebtedness and low local wages under programmes like MGNREGA reinforce this trend. The municipality also suffers from poor urban infrastructure, inadequate sanitation, and periodic social tensions, all of which contribute to urban insecurity (Bhadrak District Administration, 2024).

In both cities, climate-induced risks, weak institutional capacity, and insufficient infrastructure amplify urban vulnerability. Enhancing resilience requires integrated land-use planning, climate-resilient infrastructure, community participation, and data-driven governance. Bhubaneswar must prioritise sustainable transport, green infrastructure, and climate-sensitive planning, while Bhadrak should strengthen disaster management, improve urban services, and enhance community preparedness. Building adaptive capacity through inclusive and evidence-based planning is vital to ensure secure and sustainable urban futures for both cities.

Comparative Socio-Economic Vulnerability Analysis of Bhadrak and Bhubaneswar

In Bhadrak, socio-economic vulnerability is particularly acute: its economy remains largely agrarian and highly sensitive to recurring climate shocks such as floods, cyclones, and saline intrusion, which repeatedly erode agricultural incomes and deepen indebtedness (India Spend 2022[xxxii]; NIDM 2023). The lack of non-farm employment and low wages compels many young people to migrate, while weak institutional capacity and poor housing infrastructure exacerbate health and social risks (Bhadrak District Administration). According to the National Institute of Disaster Management (NIDM), Bhadrak has one of the highest socio-economic vulnerability indices among Odisha’s coastal districts (NIDM, 2023)[xxxiii]. In contrast, Bhubaneswar’s socio-economic insecurity is driven by rapid urbanisation and inequality: a significant portion of its population lives in informal settlements with inadequate sanitation, insecure housing tenure, and poor access to basic services (IIHS, 2020; Down To Earth, 2020)[xxxiv]. Moreover, informal-sector workers in the city face unstable incomes and no social security, while heat stress in urban “hotspots” reduces productivity and causes economic losses (Panda et al., 2018; iForest study 2025). Although Bhubaneswar is exposed to climate risks like flooding and extreme heat, it benefits from relatively stronger governance, disaster management, and economic diversification, which buffer some of the vulnerabilities (IIHS, 2020)[xxxv]. Overall, Bhadrak experiences higher socio-economic vulnerability than Bhubaneswar due to its strong dependence on climate-sensitive livelihoods. Most households rely on agriculture and fishing, making their earnings highly unstable during floods, cyclones, and saline intrusion. Recurrent climate disasters cause repeated crop losses, damaged houses, and long-term economic stress. Limited non-farm employment opportunities and weaker institutional capacity further intensify vulnerability, as the district lacks robust disaster-management systems, efficient drainage, and resilient housing. As a result, migration from Bhadrak is largely distress-driven, with many families moving out due to economic compulsion. In contrast, Bhubaneswar, while facing significant urban inequality and a large informal workforce, benefits from more diverse livelihood options, stronger governance, and infrastructural improvements under Smart City and urban development programmes. Migration to Bhubaneswar is mostly opportunity-led, driven by education and employment prospects. Overall, fewer safety nets, greater poverty, and repeated climate shocks make Bhadrak more socio-economically vulnerable than Bhubaneswar.

CONCLUSION

The comparative analysis of urban out-migration from Bhadrak and Bhubaneswar reveals distinct yet interconnected migration dynamics shaped by environmental, economic, and social factors. Bhadrak’s out-migration primarily reflects push-driven movements arising from limited livelihood opportunities, recurrent climate shocks, and rural economic stagnation. In contrast, Bhubaneswar’s out-migration is largely pull-oriented, driven by the pursuit of education, employment diversification, and improved living standards. Gender-wise variations highlight that male migrants predominantly move for work and business, whereas female migrants are influenced by social factors such as marriage and household movement, though education-driven female migration is gradually increasing in urban areas. Overall, the findings demonstrate that migration in Odisha operates as both a survival strategy and a pathway to opportunity. The study underscores the need for targeted policy interventions aimed at strengthening livelihood resilience in climate-vulnerable districts like Bhadrak and ensuring sustainable urban development in growth centres like Bhubaneswar. Promoting balanced regional development, enhancing educational access, and addressing climate-induced insecurities are crucial to managing future migration flows in a socially and economically inclusive manner.

To address the underlying causes of out-migration, it is essential to strengthen local employment opportunities through the promotion of small-scale industries, rural entrepreneurship, and climate-resilient livelihood programs in Bhadrak. Enhanced investment in education, skill training, and infrastructure can reduce the compulsion to migrate. For Bhubaneswar, migration management policies should focus on urban governance and inclusion, ensuring adequate housing, social security, and access to public services for migrant households. Moreover, establishing a migration information system at the district level can help track mobility patterns and guide evidence-based planning. Overall, migration should be viewed not merely as a challenge but as a potential driver of development if effectively managed.

World Bank, Groundswell Part II: Acting on Internal Climate Migration (Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2021), https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36248.

International Organization for Migration (IOM), World Migration Report 2020 (Geneva: International Organization for Migration, 2020), https://publications.iom.int/books/world-migration-report-2020.

No Files Found

Share Your Publication :